Sunday, August 28, 2011

Friday, August 26, 2011

Slavoj Žižek

Here's a talk on "What does it mean to be a revolutionary today?" that I'm about to watch. And here he is talking about slightly less dangerous (but no less interesting) ideas. Žižek ran for president of Slovenia once. Can you imagine what a country would be like if this guy ran it? I CAN'T EITHER!

New Chomsky piece - American Decline: Causes and Consequences

Christ, I may as well rename this thing to "The Howard Zinn and Noam Chomsky blog"

Chomsky argues that the reason why the U.S. is on the decline is because it's losing control of regions it's typically been exploiting. This loosening of imperialism has been going on for decades. He believes that the U.S.'s most recent actions/interests in the Middle East, with Egypt and with Libya, are nothing but power grabs for a region it's trying to gain control over.

A further danger to US hegemony was the possibility of meaningful moves towards democracy. New York Times executive editor Bill Keller writes movingly of Washington’s “yearning to embrace the aspiring democrats across North Africa and the Middle East.” But recent polls of Arab opinion reveal very clearly that functioning democracy where public opinion influences policy would be disastrous for Washington. Not surprisingly, the first few steps in Egypt's foreign policy after ousting Mubarak have been strongly opposed by the US and its Israeli client.

It makes a lot of sense. In the 60s and 70s, post-Chinese revolution, we lost control of the region, and so we just couldn't stop invading countries in Asia. In the 80s, we began losing control of South America, and so we couldn't leave them alone. Now look at us. The only evil dictators we care about are in the Middle East. We're carrying out military operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, and Libya. Maybe more, those are only the ones off the top of my head. In 2007, Dick Cheney tried to convince the president to bomb Syria. Bush refused. Three months later, Israel bombed Syria. I'm now beginning to see why Chomsky has described Israel as basically an American colony.

Furthermore, he demolishes the current political climate.

In parallel, the cost of elections skyrocketed, driving both parties even deeper into corporate pockets. What remains of political democracy has been undermined further as both parties have turned to auctioning congressional leadership positions. Political economist Thomas Ferguson observes that “uniquely among legislatures in the developed world, U.S. congressional parties now post prices for key slots in the lawmaking process.” The legislators who fund the party get the posts, virtually compelling them to become servants of private capital even beyond the norm. The result, Ferguson continues, is that debates “rely heavily on the endless repetition of a handful of slogans that have been battle tested for their appeal to national investor blocs and interest groups that the leadership relies on for resources.”

The post-Golden Age economy is enacting a nightmare envisaged by the classical economists, Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Both recognized that if British merchants and manufacturers invested abroad and relied on imports, they would profit, but England would suffer. Both hoped that these consequences would be averted by home bias, a preference to do business in the home country and see it grow and develop. Ricardo hoped that thanks to home bias, most men of property would “be satisfied with the low rate of profits in their own country, rather than seek a more advantageous employment for their wealth in foreign nations.

In the past 30 years, the “masters of mankind,” as Smith called them, have abandoned any sentimental concern for the welfare of their own society, concentrating instead on short-term gain and huge bonuses, the country be damned – as long as the powerful nanny state remains intact to serve their interests.

[...]

By shredding the remnants of political democracy, they lay the basis for carrying the lethal process forward – as long as their victims are willing to suffer in silence.

You should read the thing for yourself, I think it's pretty brilliant. Here's a video that was embedded in the article, it's an Al Jazeera interview of Chomsky from 2007 where he talks about much of the same stuff.

Thursday, August 25, 2011

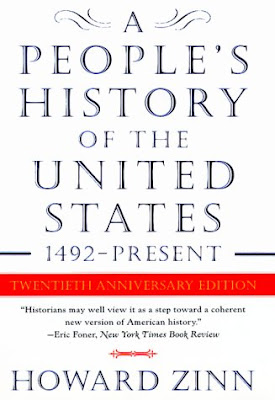

A People's History of the United States is up online for free

HERE YOU GO

I've raved about this book more than once, and now you get to see why. I'm not asking you to read this entire thing, just thumb through the chapters that you think would be interesting, see if anything sticks out at you. Hopefully if you like it, you'll be motivated to buy a real copy, which is exactly what this website is hoping you will do. Have fun.

The people behind Deadliest Warrior are cocksuckers

So I guess tonight on Spike TV's Deadliest Warrior, they put Theodore Roosevelt up against Lawrence of Arabia. No, really. I stopped watching this show halfway through the first episode because I quickly learned that it was a giant pile of horseshit, and so I was unaware that they had moved beyond specific soldier types (i.e., samurai, roman centurions) and moved on to actual historical figures. You can watch the first fifteen minutes if you want a good laugh. I couldn't make it past a couple minutes. Roosevelt won.

I was curious to know what kind of other horrifying monstrosities this show conjured, and so I looked up a list of episodes. You can easily guess the result of these matchups by just looking at whoever the American was. The American guy always wins. Did you know George Washington could beat Napoleon Bonaparte? I mean, it's almost as if these fucking idiots have never read anything about history in their entire god damn lives. Washington was a mediocre tactician at best, oftentimes bordering on incompetent. I'm not lying. The New York and New Jersey campaigns were god damn fiascos, and Washington basically did everything wrong. He came extremely close to being relieved of command by Congress. He would learn more as the war progressed (he had never before commanded an army when the war broke out), but even at his best Washington wouldn't stand a chance against Napoleon fucking Bonaparte. You may as well give George McClellan's army a bunch of swords and put him up against Hannibal Barca. What the christ.

The Deadliest Warrior wiki (it exists) described Napoleon as a "bloodthirsty French Emperor whose maniacal dream was to conquer the world" so it's not like they were biased or anything. I mean, I'm no Napoleon apologist, but the guy wasn't a sociopath for christsake. Holy shit I am so angry right now. If this is the only exposure to history the general public gets, then small wonder nobody knows fucking shit about history. This is why right wingers are able to make shit up American history and get away with it. God pissing damn it.

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

Generation OS13: The New Culture of Resistance

Monday, August 22, 2011

Mario Savio, December 2, 1964

Sunday, August 21, 2011

On Libya

I tuned into Al Jazeera completely at random last night, and I saw that the rebels were launching an attack against the capital. I checked it out today, and watched as the reports slowly came in.

A Libyan government official said on Sunday that 376 people were killed and more than 1,000 wounded in a rebel assault on the capital.

"There are 376 dead and more than 1,000 wounded" since the attacks were launched late on Saturday, the official told foreign journalists, asking not to be named.

- Libyan opposition fighters say they have entered the Green Square in central Tripoli. They said they entered the capital from the west and are about eight kilometres from the centre of the city.

Hundreds of euphoric Libyan rebels have overrun a major military base defending the capital, carting away truckloads of weapons and racing to the outskirts of Tripoli with virtually no resistance.

The rebels' surprising and speedy leap forward, after six months of largely deadlocked civil war, was packed into just a few dramatic hours.

By nightfall, they had advanced more than 20 miles to the edge of Gaddafi's last major bastion of support, entering the city's Green Square.

Along the way, they freed several hundred prisoners from a regime lockup.

Watching a live picture of crowds celebrating in Benghazi as reporters were continuously updating, was really fucking exciting. At the moment, two of Gadaffi's sons have been captured, and Gadaffi is rumored to have fled the country. Tripoli's "Green Square" is being renamed to "Martyr's Square." Since the war began, everyone had been saying the capital was incredibly loyal to Gadaffi, but they rose up and ran into the streets as soon as the rebels arrived.

Here's an Al Jazeera correspondant reporting from Tripoli only half an hour ago:

NATO undoubtedly got involved because of Libya's massive oil reserves. Syria, on the other hand, has been massacring people. Syrian gunboats have fired directly into the coastal city of Latakia, and 25 people are confirmed dead. Syria's oil exports in recent months have been outstripping its domestic need. So we don't help the people of Syria.

That said, I can't really sit here and condemn NATO. This revolution wouldn't have been won without them, and Libyans did overwhelmingly want their help. Sure, Libyans may soon be forced to become pawns for the west, but it's sure as hell a much better arrangement than what they've had. Back in March, a Libyan woman interrupted a press conference with western journalists, and screamed that Gadaffi's men had gang raped her in a secret prison. She was dragged away by armed guards as journalists struggled to help her, and went missing for three days.

NATO also likely got involved because of Libya's geographic position. Libya is in between Tunisia and Egypt, and now half of northern Africa is welcoming of democratic governments.

Libya's society is very tribal, and it will be extremely difficult forming a new government that satisfies everybody. We may see more violence. But as arabist said on twitter, "For those worrying about #Libya’s future: it might get worse, but it has never had a better chance to get better."

American media was once again a failure. I noticed American news didn't jump on the train until the battle for Tripoli was already well under way, and practically won. Fox earlier was bordering on outright racism, as a correspondent suggested that the Libyans just weren't competent enough to form a government on their own, and they'll need help. NATO will likely nudge its way in and give their help whether they want it or not.

The primary concern of American media is profits, and so they naturally aren't going to give a shit about things like this. An alternate media is essential if you want to be a somewhat informed citizen, so here are the sources I depend on the most:

Al Jazeera was kicked off American airwaves in the wake of 9/11, largely due to a mix of racism, and censorship. Al Jazeera is not based in the United States, so it's not going to be afraid to be critical of American policy when criticism is needed. Now, you'll find most right wingers are convinced it's run by terrorists, when Al Jazeera English really isn't all that different from the BBC. A live feed is up online, and can be watched at any time. You should watch it right now in fact, the celebrations are incredibly moving.

Aside from MSNBC's prime time, Democracy Now! is probably the only news source in the country that can be called "liberal." I don't like MSNBC because it mostly just turns into shouting matches where nothing is accomplished, but Democracy Now! moves past all the partisan dick waving and actually tries to inform you of what's happening. It clearly separates fact from opinion, where that line is always blurred in the mainstream press. You can subscribe to the podcast on iTunes, and get the full one-hour episode downloaded straight to your computer daily.

Tumblr. No, really. It's not all stupid hipster pictures, there are actually really informed people on there if you know where to look. If you do a search for a specific topic, you'll find people who are much more obsessed over this stuff than I am. I guess you could replace "tumblr" with "twitter" if you're on that, but I'm not.

And of course, there's reddit. Worldnews is great for this stuff.

Congratulations to Libya for ousting a murderous shithead. I hope he's caught, tried, and executed. In closing, I think I'm going to post this spectacular video again, because I always look for excuses to do so.

Saturday, August 20, 2011

The Spanish-American War, the Philippines, and American Imperialism

So like I mentioned in that other post, I'm going through A People's History right now. I want to share this one part about American imperialism at the turn of the century that I found really interesting.

The war in the Philippines came directly out of the Spanish-American war. The Cubans were already in revolt against the Spanish at the time the war broke out. The U.S. government claimed one of the reasons for the war was to support the oppressed Cuban rebels. We had a just cause. We ignored them entirely once we got there. Corporations arrived just as quickly as the boots of marines, and we proceeded to take the place of the Spanish. The rebels were cut out from the peace negotiations. Rebel general Calixto García wrote a letter of protest to American general William Shafter:

I have not been honored with a single word from yourself informing me about the negotiations for peace or the terms of the capitulation by the Spaniards.

. . . when the question arises of appointing authorities in Santiago de Cuba . . . I cannot see but with the deepest regret that such authorities are not elected by the Cuban people, but are the same ones selected by the Queen of Spain. . . .

A rumor too absurd to be believed, General, describes the reason of your measures and of the orders forbidding my army to enter Santiago for fear of massacres and revenge against the Spaniards. Allow me, sir, to protest against even the shadow of such an idea. We are not savages ignoring the rules of civilized warfare. We are a poor, ragged army, as ragged and poor as was the army of your forefathers in their noble war for independence. . .

At the end of the war, the United States acquired Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippine Islands. President McKinley didn't even want the Philippines at first. It was all the way next to Australia, and he didn't really know what to do with it. But the Filipinos would be lost without white people telling them what to do. ". . . [T]hey were unfit for self-government--and they would soon have anarchy and misrule over there worse than Spain's was." We had to "uplift and civilize and Christianize them, and by God's grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellow men for whom Christ also died." These are McKinley's words.

The Filipinos rose up in rebellion, striving for self-government, and they received God's love McKinley described, in the language of bullets and massacres. Our government didn't even try to hide its imperialist interests. Senator Albert Beveridge said on January 9, 1900:

The Philippines are ours forever. . . And beyond the Philippines are China's illimitable markets. We will not retreat from either. . . . We will not renounce our part in the mission of our race, trustee, under God, of the civilization of the world. . . . The Pacific is our ocean. . . . Where shall we turn for consumers of our surplus? Geography answers the question. China is our natural customer. . . . The Philippines give us a base at the door of all the East. . . .

It has been charged that our conduct of the war has been cruel. Senators, it has been the reverse. . . . Senators must remember that we are not dealing with Americans or Europeans. We are dealing with Orientals.

A small group of American intellectuals formed the Anti-Imperialist League in response to the war. A soldier from Kansas wrote to them:

Caloocan was supposed to contain 17,000 inhabitants. The Twentieth Kansas swept through it, and now Caloocan contains not one living native.

A volunteer from the state of Washington wrote:

Our fighting blood was up, and we all wanted to kill niggers. . . . This shooting human beings beats rabbit hunting all to pieces.

A Manila correspondent wrote in November 1901:

. . . our men have been relentless, have killed to exterminate men, women, children, prisoners, and captives, active insurgents and suspected people from lads of ten up, the idea prevailing that the Filipino as such as little better than a dog. . . . Our soldiers have pumped salt water into men to make them talk, and have taken prisoners people who held up their hands and peacefully surrendered, and an hour later, without an atom of evidence to show that they were even insurrectos, stood them on a bridge and shot them down one by one, to drop into the water below and float down, as examples to those who found their bullet-loaded corpses.

A major named Littletown Waller was accused of massacring eleven defenseless Filipinos. Other marine officers described the testimony:

The major said that General Smith instructed him to kill and burn, and said that the more he killed and burned the better pleased he would be; that it was no time to take prisoners, and that he was to make Samar a howling wilderness. Major Waller asked General Smith to define the age limit for killing, and he replied "Everything over ten."

Black American soldiers started seeing parallels to how they were treating the Filipinos, and how they themselves were treated by whites. One black soldier, William Simms, wrote:

I was struck by a question a little Filipino boy asked me, which ran about this way: "Why does the American Negro come . . . to fight us where we are much a friend to him and have not done anything to him. He is all the same as me and me all the same as you. Why don't you fight those people in America who burn Negroes, that make a beast of you . . . ?"

Many black soldiers defected, and started to fight for the Filipinos. The most famous of these was David Fagan, who "accepted a commission in the insurgent army and for two years wreaked havoc upon the American forces." Source:

David Fagen was the most celebrated of the handful of African American soldiers who defected to the Filipino revolutionary army led by Emilio Aguinaldo during the Filipino American War of 1899-1902. Fagen was born in Tampa, Florida around 1875. Details of his life remain sketchy. His father was a merchant and a widower. For a time he worked as a laborer for Hull’s Phosphate Company.

On June 4, 1898 at the age of 23, Fagen enlisted in the Twenty-fourth infantry, one of the four black regiments of that time that was coincidentally based in Tampa. Fagen would see combat a year later as he shipped off from San Francisco to Manila on June 1899. By then, the Filipino American war had been raging for four months, as Filipino patriots sought to defend their newly established Republic which they had won in a revolution against Spain. Fagen was soon in combat against Filipino guerillas in Central Luzon. Reports indicate that he had constant arguments with his commanding officers and requested to be transferred at least three times which contributed to his growing resentment of the army.

On Nov. 17, 1899, Fagen defected to the Filipino army. Winning the trust of the Filipinos he took sanctuary in the guerilla-controlled areas around Mount Arayat in Pampanga province. Fagen served enthusiastically for the next two years in the Filipino cause. His bravery and audacity were much praised by his Filipino comrades. Fagen was promoted from first lieutenant to captain by his commanding officer, General Jose Alejandrino on Sept. 6, 1900. Such was his popularity that Filipino soldiers often referred to him as “General Fagen.” His exploits earned him front page coverage in the New York Times which described him as a “cunning and highly skilled guerilla officer who harassed and evaded large conventional American units.”

Clashing at least eight times with American troops from Aug. 30, 1900 to Jan. 17, 1901, Fagen’s most famous action was the daring capture of a steam launch on the Pampanga River. Along with his men, he seized its cargo of guns and swiftly disappeared into the forests before the American cavalry could arrive. White officers were frustrated at their inability to capture Fagen whose exploits by now had begun to take on legendary proportions both among the Filipinos and in the U.S. press. Fagen’s success also triggered the fear of black defections (of which there were actually only twenty).

By 1901, American forces captured key Filipino leaders including Alejandrino and by March, Aguinaldo himself. Filipino leaders tried to secure amnesty for Fagen, but the Americans refused, insisting that he would be court-martialed and most likely executed. Hearing of this, Fagen, by now married to a Filipina, refused to surrender and sought refuge in the mountains of Nueva Ecija in Central Luzon. Branded a “bandit,” Fagen became the object of a relentless manhunt, with a $600 reward for his capture, “dead or alive.” Posters of him in Tagalog and Spanish appeared in every Nueva Ecija town, but he continued to elude capture.

On Dec. 5, 1901, Anastacio Bartolome, a Tagalog hunter, delivered to American authorities the severed head of a “negro” he claimed to be Fagen. While traveling with his hunting party, Bartolome reported that he had spied upon Fagen and his wife accompanied by a group of indigenous people called Aetas bathing in a river. Recognizing him from the wanted posters, the hunters attacked the group and allegedly killed and beheaded Fagen, then buried his body near the river. But this story has never been confirmed and there is no record of Bartolome receiving a reward. Official army records of the incident refer to it as the “supposed killing of David Fagen,” and several months later, Philippine Constabulary reports still made references to occasional sightings of Fagen.

To this day, it remain unclear what exactly became of David Fagen. His life after the war continued to be as mysterious as his existence before it. But his actions, largely forgotten in the United States, continue to be remembered in the Philippines as that of an African American man who heroically cast his lot with the Filipino revolutionaries to resist the injustice of American imperial designs.

History is important. The history we would rather forget is especially important. More than anything, history gives us a blueprint to how power acts. Power is sociopathic. It disassociates itself from the human impact. It's why U.S. officials described Hawaii in 1898 as "a ripe pear ready to be plucked." It's why the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations in 1996 described the deaths of half a million children in the First Gulf War as "worth it." We can easily get to sleep at night thinking that we're somehow wiser than we were only a hundred years ago. What people have a hard time grasping is just how connected we are to this. Our grandparents knew people who fought in these wars. This was not a long time ago. We're being run by the exact same government, the exact same corporations, the exact same people. Nothing has changed. That's why no matter what, we should never, ever stop yelling.

Friday, August 19, 2011

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

Summer Reading Recommendations

This book is very biased, and Zinn writes a disclaimer admitting it. His goal with this book was to tell the story of the oppressed, rather than from the sugarcoated perspective we normally see in history. I would not recommend you start this if you don't already know a thing or two about American history already, so that you can fairly weigh his arguments and disagree with them if you want. For example, I felt that his treatment of the founders was a little unfair. He criticizes them for forming a republic that mostly benefited the elite (true), rather than focusing a social democracy. While certainly valid, I felt that it was a little unfair since Marx and Engels wouldn't write the manifesto until a century later, and they were never exposed to those ideas.

I'm still not through with it yet. It's pretty massive. But that's the great thing about most nonfiction. You can put it down and pick it back up over the course of a few months, like with I've been doing. I'm in the late 1800s/early 1900s right now, and he's going over all the union struggles, and the government's collaboration with business to stamp them out. I'm learning a shit ton of great new info that all my other history books completely breezed over. This book is pretty essential if you want a full picture.

Zinn has a companion book called Voices of a People's History of the United States, which I haven't picked up yet. It's a collection of essays, letters, speeches, and other forms of written word, directly out of the mouths of the people who lived in the eras. I can't wait. Here's an excellent excerpt I found on youtube. This is Josh Brolin reading a statement from pre-Civil War hero John Brown at his court hearing, who led armed insurrection at Harper's Ferry in the hopes of sparking a slave revolution.

And here's Sandra Oh reading Yuri Kochiyama, a Japanese American who was put into a concentration camp during World War II. I couldn't decide which video I liked better, so yeah here's both. Can you understand why I can't fucking wait to get to this? I mean Christ, this almost made me tear up.

You can skip over the history stuff if you're not into it, but Empire of Illusion is an absolutely must-read. Hedges describes in excruciating detail just how braindead our society is, and attempts to explain how we got here. This is very grim. He makes a convincing argument that everything is basically hopeless, and all it will take for fascism to arise in the United States is one more 9/11-type disaster, and a demagogue to take advantage of it. He sees little hope, and is convinced that if drastic action is not taken immediately to counteract this illiterate, delusional society, we'll just slip further and further, and soon go the way of Weimar.

I feel that it's a little unsafe to base your entire worldview on only one person, but I really can't help it in this case. In high school it was Gandhi, and now I guess it's becoming Noam Chomsky. Reading this book has shifted the lens through which I view the world. You can't say that very many times throughout your life. This is what changed me from being disappointed with Obama and the Democratic party, to advocating tearing down the entire bullshit corrupt corporatist system, and starting anew. This is what convinced me that socialism is a good idea. Understanding Power is a collection of lectures Chomsky has given over the decades, and given that all of his opinions are in one compact place, this seems like the best place to start with him. Can't recommend it enough.

Sunday, August 14, 2011

Saturday, August 6, 2011

Noam Chomsky on whether human nature is inherently corrupt, and on moral values

Well, there's a sense in which the claim is certainly true. First of all, human nature is something we don't know much about: doubtless there is a rich and complex human nature, and doubtless it's largely genetically determined, like everything else--but we don't know what it is. However, there is enough evidence from history and experience to demonstrate that human nature is entirely consistent with everything you mentioned--in fact, by definition it has to be. So we know that human nature, and that includes our nature, yours and mine, can very easily turn people into quite efficient torturers and mass-murderers and slave-drivers. We know that--you don't have to look very far for evidence. But what does that mean? Should people therefore not try to stop torture? If you see somebody beating a child to death, should you say, "Well, you know, that's human nature"--which it is in fact: there certainly are conditions under which people will act like that.

To the extent that the statement is true, and there is such an extent, it's just not relevant: human nature also has the capacity to lead to selflessness, and cooperation, and sacrifice, and support, and solidarity, and tremendous courage, and lots of other things too.

I mean, my general feeling is that over time, there's measurable progress--it's not huge, but it's significant. And sometimes it's been pretty dramatic. Over history, there's been a real widening of the moral realm, I think--a recognition of broader and broader domains of individuals who are regarded as moral agents, meaning having rights. Look, we are self-conscious beings, we're not rocks, and we can come to get a better understanding of our own nature, it can become more and more realized over time--not because you read a book about it, the book doesn't have anything to tell you, because nobody really knows anything about this topic. But just through experience--including historical experience, which is part of our personal experience because it's embedded in the culture we enter into--we can gain greater understanding of our nature and values.

Take the treatment of children, for example. In the medieval period, it was considered quite legitimate to either kill them, or throw them out, or treat them brutally, all sorts of things. It still happens of course, but now it's regarded as pathological, not proper. Well, it's not that we have a different moral capacity than people did in the Middle Ages, it's just that the situation's changed: there are opportunities to think about things that weren't available in a society that had a lower material production level and so on. So we've just learned more about our own moral sense in that area.

I think it's part of moral progress to be able to face things that once looked as if they weren't problems. I have that kind of feeling about our relation to animals, for example--I think the questions there are hard, in fact. A lot of these things are matters of trying to explore your own moral intuitions, and if you've never explored them, you don't know what they are. Abortion's a similar case--there are complicated moral issues. Feminist issues were a similar case. Slavery was a similar case. I mean, some of these things seem easy now, because we've solved them and there's a kind of shared consensus--but I think it's a very good thing that people are asking questions these days about, say, animals rights. I think there are serious questions there. Like, to what extent do we have a right to experiment on and torture animals? I mean, yes, you want to do animal experimentation for the prevention of diseases. But what's the balance, where's the trade-off? There's obviously got to be some. Like, we'd all agree that too much torture of animals for treating a disease would not permissible. But what are the principles on which we draw such conclusions? That's not a trivial question.

MAN: What about eating?

Same question.

MAN: Are you a vegetarian?

I'm not, but I think it's a serious question. If you want my guess, my guess is that if society continues to develop without catastrophe on something like the course you can see over time, I wouldn't in the least be surprised if it moves in the direction of vegetarianism and the protection of animal rights.

Look, doubtless there's plenty of hypocrisy and confusion and everything else about the question right now, but that doesn't mean that the issue isn't valid. And I think one can see the moral force to it--definitely one should keep an open mind on it, it's certainly a perfectly intelligible idea to us.

I mean, you don't have to go back every far in history to find gratuitous torture of animals. So in Cartesian philosophy, they thought they'd proven that humans had minds and everything else in the world was a machine--so there's no difference between a cat and a watch, let's say, just the cat's a little more complicated. And if you look back at the French Court in the seventeenth century, courtiers--you know, big smart guys who'd studied all this stuff and thought they understood it--would as a sport take Lady So-And-So's favorite dog and kick it and beat it to death, and laugh, saying, "Ha, ha, look, this silly lady doesn't understand the latest philosophy, which shows that it's just like dropping a rock on the floor." That was gratuitous torture of animals, and it was regarded as if it were the torturing of a rock; you can't do it, there's no way to torture a rock. Well, the moral sphere has certainly changed in that respect--gratuitous torture of animals is no longer considered quite legitimate.

MAN: But in that case it could be that what's changed is our understanding of what an animal is, not the understanding of our underlying values.

In that case it probably was--because in fact the Cartesian view was a departure from the traditional view, in which you didn't torture animals gratuitously. On the other hand, there are cultures, like say aristocratic cultures, that have fox-hunting as a sport, or bear-baiting, or other things like that, in which gratuitous torture of animals has been seen as perfectly legitimate.

In fact, it's kind of intriguing to see how we regard this. Take cock-fighting, for example, in which cocks are trained to tear each other to shreds. Our culture happens to regard that as barbaric; on the other hand, we train humans to tear each other to shreds--they're called boxing matches--and that's not regarded as barbaric. So there are things that we don't permit of cocks that we permit of poor people. Well, you know, there are some funny values at work there.

MAN: You mentioned abortion--what's your view about that whole debate?

I think it's a hard one, I don't think the answers are simple--it's a case where there really are conflicting values. See, it's very rare in most human situations that there's a clear and simple answer about what's right, and sometimes the answers are very murky, because there are different values, and values do conflict. I mean, our understanding of our own moral value system is that it's not like an axiom system, where there's always one answer and not some other answer. Rather we have what appear to be conflicting values, which often lead us to different answers--maybe because we don't understand all the values well enough yet, or maybe because they really are in conflict. Well, in the case of abortion, there are just straight conflicts. From one point of view, a child up to a certain point is an organ of the mother's body, and the mother ought to have a decision what to do--and that's true. From another point of view, the organism is a potential human being, and it has rights. And those two values are simply in conflict.

On the other hand, a biologist I know once suggested that we may one day be able to see the same conflict when a woman washes her hands. I mean, when a woman washes her hands, a lot of cells flake off--and in principle, each of those cells has the genetic instructions for a human being. Well, you could imagine a future technology which would take one of those cells, and create a human being from it. Now, obviously he was making the argument as a reductio ad absurdum argument, but there's an element of truth to it--not that much yet, but it's not like saying something about astrology. What he's saying is true.

If you want to know my own personal judgment, I would say a reasonable proposal at this point is that the fetus changes from an organ to a person when it becomes viable--but certainly that's arguable. And besides, as this biologist was pointing out, it's not very clear when that is--depending on the state of technology, it could be when the woman's washing her hands. That's life, though: in life you're faced with hard decisions, conflicting values.

Saturday Youtube Post

CASSINI MISSION from Chris Abbas on Vimeo.

Friday, August 5, 2011

Malcolm X at the Oxford Union, 1967

Tuesday, August 2, 2011

Keith's reaction to the debt ceiling deal - Get mad.

The betrayal of what this nation was supposed to be about did not begin with this deal and it surely will not end with this deal. There is a tide pushing back the rights of each of us, and it has been artificially induced by union bashing, and the sowing of hatreds and fears, and now this evermore institutionalized economic battering of the average American. It will continue and it will crush us, because those that created it are organized, and unified, and hell-bent. And the only response is to be organized, and unified and hell-bent in return.

Is it bad that my eyes rolled instinctively when he said "We must rise, nonviolently"? I think people should start smashing shit in the streets, personally. How many more times are we going to let the upper 1% do this to us? Are we ever going to draw a line, or are we just going let them keep at that successful tactic of chipping away, little by little?

But Keith is also on television, so I guess he can't just go and incite riots if he doesn't want to get thrown in jail. I came across an essay the other day called Pacifism as Pathology, which I'm pretty sure was written by an anarchist. The guy strongly criticizes the pacifist peace movement as entirely useless, claims it's never accomplished a thing, and dismisses it as pseudospiritual nonsense, almost like a cult. Considering that this is the tactic liberals have been using since the 60s, and considering that what it's accomplished is where we're at now, I find myself agreeing with this assessment more than I'm disagreeing with it. If I wind up dead under mysterious circumstances, I didn't commit suicide.

Pacifism, the ideology of nonviolent political action, has become axiomatic and all but universal among the more progressive elements of contemporary mainstream North America. With a jargon ranging from a peculiar mishmash of borrowed or fabricated pseudospiritualism to “Gramscian” notions of prefigurative socialization, pacifism appears as the common denominator linking otherwise disparate “white dissident” groupings. Always, it promises that the harsh realities of state power can be transcended via good feelings and purity of purpose rather than by self-defense and resort to combat.

Pacifists, with seemingly endless repetition, pronounce that the negativity of the modern corporate-fascist state will atrophy through defection and neglect once there is a sufficiently positive social vision to take its place (“What if they gave a war and nobody came?”). Known in the Middle Ages as alchemy, such insistence on the repetition of insubstantial themes and failed experiments to obtain a desired result has long been consigned to the realm of fantasy, discarded by all but the most wishful or cynical (who use it to manipulate people).

Monday, August 1, 2011

Reconstructionist South

Mr. Speaker. . . . I wish the members of this House to understand the position that I take. I hold that I am a member of this body. Therefore, sir, I shall neither fawn or cringe before any party, nor stoop to beg them for my rights. . . . I am here to demand my rights, and to hurl thunderbolts at the men who would dare to cross the threshold of my manhood. . . .

The scene presented in this House, today, is one unparalleled in the history of the world. . . . Never, in the history of the world, has a man been arraigned before a body clothed with legislative, judicial or executive functions, charged with the offense of being of a darker hue than his fellow men. . . . it has remained for the State of Georgia, in the very heart of the nineteenth century, to call a man before the bar, and there charge him with an act for which he is no more responsible than for the head which he carries upon his shoulders. The Anglo-Saxon race, sir, is a most surprising one. . . . I was not aware that there was in the character of that race so much cowardice, or so much pusillanimity. . . . I tell you, sir, that this is a question which will not die today. This event shall be remembered by posterity for ages yet to come, and while the sun shall continue to climb the hills of heaven. . . .

We are told that if black men want to speak, they must speak through white trumpets; if black men want their sentiments expressed, they must be adulterated and sent through white messengers, who will quibble, and equivocate, and evade, as rapidly as the pendulum of a clock. . . .

The great question, sir is this: Am I a man? If I am such, I claim the rights of a man. . . .

Why, sir, though we are not white, we have accomplished much. We have pioneered civilization here; we have built up your country; we have worked in your fields, and garnered your harvests, for two hundred and fifty years! And what do we ask of you in return? Do we ask you for compensation for the sweat our fathers bore for you--for the tears you have caused, and the hearts you have broken, and the lives you have curtailed, and the blood you have spilled? Do we ask for retaliation? We ask it not. We are willing to let the dead past bury its dead; but we ask you now for our RIGHTS. . . .